By Jessica Bartlett and Marin Wolf Globe Staff

Each time one of Tamara Modig’s children needs a telehealth appointment, she boots up a fragile 13-year-old laptop and prays it’ll hold a charge.

Then Modig is forced to fret with another concern: the cost of health care.

The Fitchburg Public Schools employee and her husband pay more than $9,300 annually in health insurance premiums for their family of five. It’s already a substantial chunk of their combined $160,000 income.

Modig knows it’s almost certainly going to rise next year, though she won’t learn how much until spring. Already, her out-of-pocket maximum this past year increased by $1,000, to $4,000. The family doesn’t take vacations, drives only used cars, and lives on a strict budget — which is about to get even stricter.

“You wonder if you can make that pair of shoes last longer,” Modig said. “Does last year’s coat still fit the kids?”

The rising price of health insurance has become top of mind in many households across the state as families like the Modigs take stock during traditional open enrollment periods. Many employers’ premiums have risen by 10 percent or more, insurers and brokers say, straining families’ budgets at a time when overall health care costs are on the rise and expected to grow even more in the coming years.

“This is the hardest health insurance market I’ve seen in two decades, with no end in sight,” said David Shore, executive vice president at Borislow Insurance, which helps companies across the East Coast, including in Massachusetts, navigate insurance and funding options. “It’s only going to get worse.”

The costs aren’t just growing — they are exacerbating an affordability crisis for state residents and businesses, experts say. The Massachusetts Taxpayers Foundation, a business-backed policy group, recently cited health care costs as a top concern, with Massachusetts having among the highest employer health care costs in the country.

Rising premiums, plus out-of-pocket health care costs, are all outpacing increases in household income, inflation, and other indicators of economic growth. As a result, Massachusetts is increasingly unaffordable to live in, said David Seltz, executive director of the state Health Policy Commission, during a recent hearing.

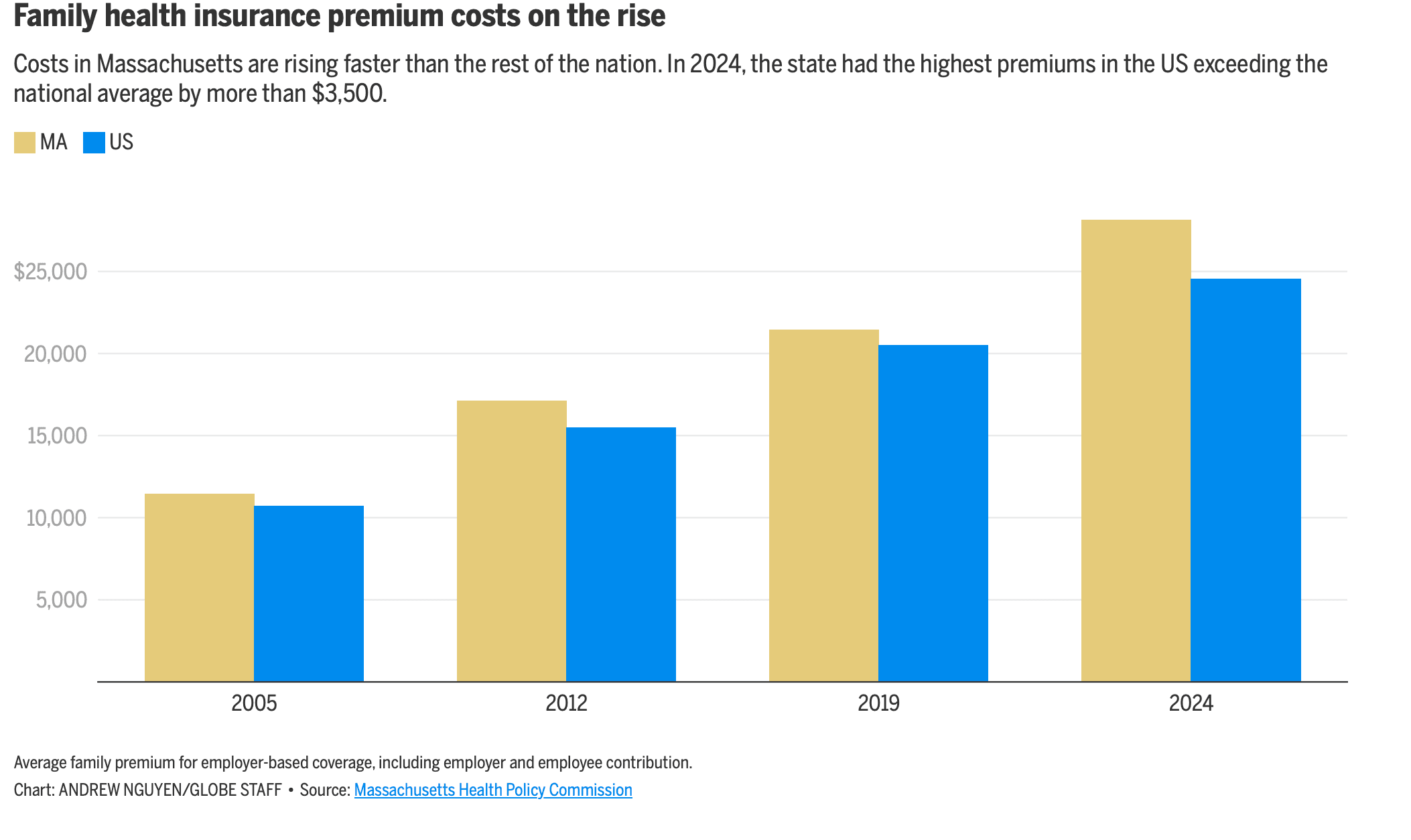

Massachusetts had the highest insurance premiums in the US last year. And the years of consistent, rising premium costs in the state have long surpassed national trends.

Families in Massachusetts spent, on average, $28,151 for employer-based health insurance last year, according to data presented by the Health Policy Commission, a state agency.

Nationally, that figure was $24,540.

Family health insurance premium costs on the rise

Costs in Massachusetts are rising faster than the rest of the nation. In 2024, the state had the highest premiums in the US exceeding the national average by more than $3,500.

And that’s just premiums. Consumers face other health care costs, including co-pays and deductibles. All told, the average annual cost of health care coverage for a family in Massachusetts was $32,469 in 2024.

Since 2024, insurance costs have grown. Family premiums for employer-sponsored health insurance grew 6 percent nationally from 2024 to 2025, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation survey of employers.

Because official data sources lag, it’s difficult to assess private insurance prices planned for 2026 in real time.

But regardless of how a person gets commercial insurance — whether purchasing for themselves on the state’s insurance marketplace, going through a broker, getting it directly from an insurer, or receiving insurance through an employer — costs are seemingly on the rise for everyone next year.

The state’s insurance exchange, where people and small businesses can buy their own insurance, has reported its premiums will increase by 11.5 percent, on average, in 2026.

Those premium increases range from 7.2 percent by Fallon Health to 13.6 percent by Boston Medical Center Health Plan, which also goes by WellSense Health Plan.

These hikes and others mean small businesses are maxed out on health care costs, said Jon Hurst, president of the Retailers Association of Massachusetts.

“We’re at a breaking point,” Hurst said.

Beyond pending retirements, profitability is flat and health care and energy costs have skyrocketed, meaning about half of small businesses in Massachusetts predicted they would have to sell or close within five years, a UMass Donahue Institute study showed in February.

For businesses, premium increases can depend on a number of factors, including an employer’s size, health care usage trends, and how the employer purchases insurance.

Less than half of Massachusetts employers are considered “fully insured,” meaning they buy insurance in which the insurer takes on the financial responsibility for paying out medical claims.

Most of the employers in this group who have 50 to 100 employees are seeing whopping premium increases that range from 10 to 30 percent, said Mark Gaunya, principal at Borislow Insurance, which works with hundreds of companies of varying sizes.

Larger employers in this bucket are more likely to see smaller price increases, he said, though things vary.

Most employers in Massachusetts, however, are considered “self-insured” as they pay for the health care claims of their employees more directly. These types of workplaces are also seeing premium increases, from low single digit to low double digits.

“I haven’t seen rate increases like this in a long, long time,” Gaunya said of the industry at large. “The market is really, really hard right now for a lot of people.”

The state’s two largest insurers cited figures that were similar. At Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, “fully-insured” employers are seeing high single to low double-digit increases on average, though numbers vary widely depending on other factors, the insurer said. For its own employees, Blue Cross passed on an average 20 percent premium increase.

At Point32Health, premiums for employers with over 50 employees are increasing by about 15 to 20 percent on average in 2026, again with considerable variability.

When confronted with ever-rising costs, employers have to get more creative with the way they offer insurance, or change what is covered. Beyond passing on the entirety of the increase to their employees as higher premiums, employers can redesign the plan, or shift more costs onto the employee. That can mean higher co-pays and deductibles, in addition to higher premiums.

“We’re seeing more 20s- and 30-percent increases than we ever have before, in premiums. It’s quite insane,” said Gregory Puig, partner with Sentinel Group and the president of the Massachusetts chapter of the National Association of Benefits and Insurance Professionals.

Shifting costs onto employees is not a new strategy.

Nearly half of Massachusetts residents with commercial insurance had a high deductible health plan in 2023 — up from 19 percent in 2014, state data show.

Average deductibles are also on the rise — from about $2,300 in 2014 to over $3,100 in 2023.

Rob DiMase, a partner at Sentinel Group, an employee benefits administration and consulting firm, said these strategies have helped some employers he works with mitigate a 20 percent cost increase for next year, so the employees only see their premiums rise by 10 to 12 percent.

Still, some employers are seeing huge increases. In the large group business, which includes employers with 50 to 500 employees, the best initial increase DiMase saw was 7 percent. The worst was around 57 percent.

Escalating costs have patients worried about the future.

Joe D’Eramo, 61, who has a broker, paid just over $615 monthly this year for coverage through WellSense. Beginning Jan. 1, that premium will increase by $90 per month and his deductible will rise by $500, to $3,500.

D’Eramo works as a freelance copy editor and public relations specialist, and drives for Uber on the side. But a $1,000 settlement with the ride share company will be wiped out by his health insurance increase.

D’Eramo, who lives in Millis, was recently diagnosed with diabetes. He is counting down the years until he qualifies for Medicare, the government insurer that generally serves people 65 and older, so that he can save more money.

“I just want to be able to make it to that [while still] healthy,” he said.

Jessica Bartlett can be reached at jessica.bartlett@globe.com. Follow her @ByJessBartlett. Marin Wolf can be reached at marin.wolf@globe.com.